Scenario planning for a post-crisis world

Scenario planning is a strategic tool designed to help organisations prepare for a range of possible futures. It is not about predicting the future. Fundamentally, it is about accommodating uncertainty.

The obvious temptation is to wait for the ‘next normal’ to emerge before thinking about the future. But what if you’re waiting for the dust to settle - and it never does?

Thinking about the future should reveal the work you need to do in the present.

Why use scenario planning?

Scenario planning was traditionally used by managers thinking about the very long-term. It became popular when the oil industry wanted to think about investments that paid back over decades.

These managers found that the discipline of considering possible futures left their organisations better prepared to face different consequences.

Is a tool designed to help the oil industry think in decades appropriate for mission-driven organisations trying to accommodate the rapidly changing environments we find ourselves in today?

We think so. Scenario planning is not about predicting the future. It is about being prepared for a range of possible futures.

How do you make scenario planning useful?

Too many scenario planning exercises feel abstract. Workshops about robots and flying cars don’t seem to connect to the real-world challenges you will face when the meeting finishes.

Connecting scenarios to implications and action is important.

Thinking about the future should reveal the work you need to do in the present.

Often the value is in reframing current challenges, or realising that your current ways of working are set up to answer the wrong question.

It’s a theme we explored in our work with the Royal Society of Chemistry. The approach we designed - and the link to strategy - is covered in this MIT Sloan Management Review article.

As the article notes:

“many senior executives are coming to the view that smart management benefits from a richer understanding of the present possibilities afforded from multiple views about possible futures.”

The big challenge is how you link the insights of a scenario planning exercise to change in your organisation.

It is important you find a way for it to “live”. Finishing a scenario planning exercise should start new conversations.

How can we apply scenario planning to the current moment?

The temptation might be to wait for the ‘next normal’ to settle before thinking about the future.

But a world of current instability and future stability is just one possible scenario.

What if you’re waiting for the dust to settle, and the dust never settles?

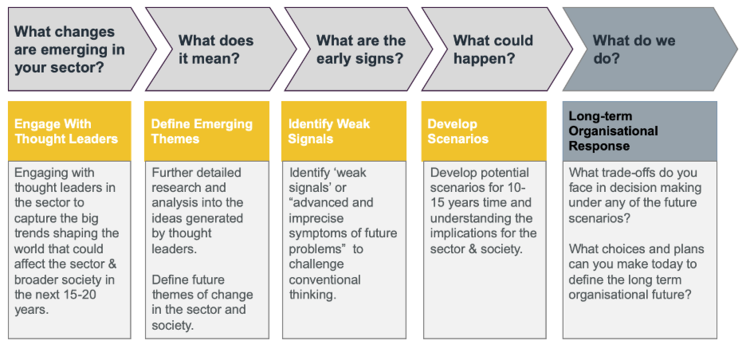

Whilst no engagement is the same, the process for developing scenarios normally follows a similar structure. The process can be highly participative where the objective is to get the benefits of an inclusive approach, or a short-term hit to stimulate fresh thinking in a leadership team.

Creating stories about potential futures starts by examining emerging trends in the present. These are distilled into broad future themes. After this, look for early signs or “weak signals” of changes that will overturn current ways of thinking.

The typical model of scenario planning is based on a 10 to 15 year time horizon. But this can be adapted to the present moment by considering shorter time horizons. What early signals of problems might you see next year that will could become material in 5 years’ time?

The second key point is to link the scenarios to action. Who will be responsible for monitoring weak signals? How and when will you decide to act on these signals? What is true in all instances? What do you need to prepare for?

A generic scenario planning process

You don’t have to start with a blank canvas

A number of useful reports on post-crisis scenarios have been published, many of which we have already featured in our fortnightly briefing. (You can sign up here if you don’t already receive it). To highlight three:

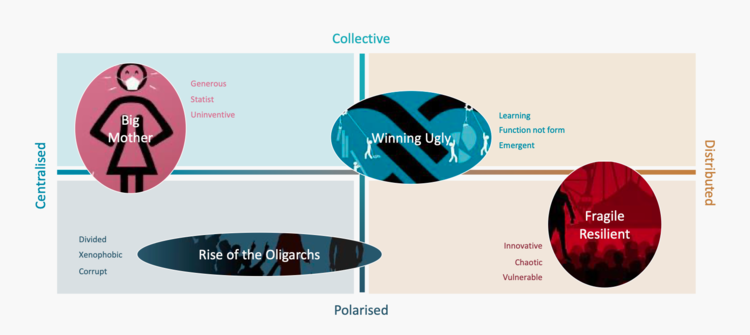

The Long Crisis Trust presents four scenarios for how the pandemic might play out. These depend on the extent to which the response is collective or polarised, and whether it is centralised or distributed.

The Deloitte Monitor Institute lays out four scenarios based on the severity of the crisis and the level of social cooperation. The scenarios point to different implications for nonprofits: from facing increased pressure to fill gaps as trust in government erodes to adopting a lean operating model und empowering the community to direct resources and shape strategy.

The Zukunftsinstitut maps four possible scenarios how the pandemic will change the way we live. In its most optimistic scenario, new patterns of consumption, a more holistic understanding of health and increased solidarity will make the world more resilient and adaptive.

To underline the point, the aim is not to choose which scenario you find most plausible.

The value comes from considering the axes of uncertainty that the scenarios are based on, and how you might respond in each case.

Final thoughts

The process of scenario planning can often be more useful than the deliverable. A good process gives a framework and common language for a group thinking about challenges ahead.

The challenge is to think about the implications of scenarios, and what you might do in different situations.

Firetail has worked across sectors with clients on scenario planning engagements of all kinds. For public sector clients, we are official suppliers of foresight work and scenario planning through the Government Office of Science’s Futures Framework. You can find our brochure here.

If you’re interested in taking to us about scenario planning, get in touch at mail@firetail.co.uk.